Should you edit photos you took on film?

Uh, hell yeah you should.

Uh, fuck yeah, you should.

The world of photography and cinematography often cycles between the forms of clean and dirty image making, often brought on by some sort of technological innovation in the medium, a rush to adopt said technology, and the subsequent bucking of the innovation it brings about. Whether it was the sudden rush for clean, crisp imagery that spawned the stupidly sharp, insanely fast lenses on any DSLR and mirrorless camera out there in the 2010s thanks to new manufacturing processes, new sensors, and innovations in imaging technology, or the said fallback to vintage and analog processes that you see today, the process of making an image has always teetered between these two worlds.

So, with the increasingly present trend being a dedication towards trying to achieve a film look, let's take a second to discuss one of the hotly debated topics in the film photography world:

Should you edit photos you took on film?

Pause, for a moment, to imagine your favorite photo. The film photo, that one which inspired you all those years ago, that one which you aspire to, that magnum opus which would complete your life's work if you could get ever so close to capturing something similar.

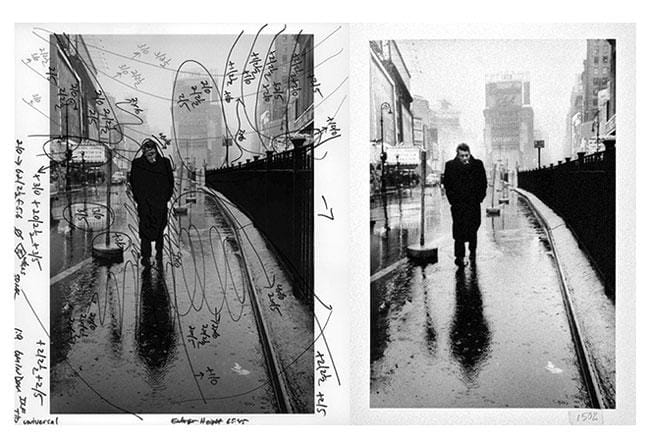

That photo, your favorite photo of all time, probably looked like shit — initially. It wasn't until that photo was taken into a darkroom, developed, evaluated, manipulated, dodge and burned, redeveloped, reevaluated, and reprinted, that it become that photo to which you aspire to.

In fact, most film photos you have ever seen in art books and inspirational collections are all manipulated in some form or another. It's part of the craft of photography– you not only are taking an image, you are making an image.

To quote

“I see no magic to a straight print (i.e., one with no darkroom manipulation, such as dodging or burning) unless the tonal values of the scene miraculously fall into the perfect array of tonalities everywhere. Such perfect alignment rarely occurs, so darkroom manipulation is almost always necessary. Ansel Adams knew this, for nearly all of his prints were burned or dodged, some quite heavily. I know this to be true because I had spoken to him about the printing of several of his images, and he explained the extensive manipulations required for most of his images. Most of my prints are manipulated as well, some quite extensively. I recommend that all photographers recognize this and use the tools available in the darkroom for their creative and artistic needs.”

— Bruce Barnbaum, The Art of Photography, page 193

So yeah, you should definitely feel fine editing your film photos.

So why do we feel like we shouldn't edit our film photos?

Unfortunately, this has to do with aesthetic. With the major trend nowadays being to dirty up the image to achieve a film look, so many people are engrossed in the aesthetic qualities of film – the grain, the colors, the quality — that any attempt to buck films natural output feels like an attempt to go against nature itself.

"Digital photos are meant to be manipulated," you say to yourself. "Everything on film feels so much more real."

But film's natural output is no more real than the same output on a digital sensor. The aesthetic is different – dirty versus clean, again — but my intention is all the same.

As a photographer, I am taking a photograph intentionally. I am making an image. My intention in taking said image— with all the considerations and decisions made in the complexities of composition, exposure, focus and lensing – is to say something with my image. I am trying to speak with my image, in the same way a painter is trying to say something with every brushstroke. Every image you take and share as a photographer is a tiny part of you shouting at the top of their lungs, "Look at this! Look at it and feel what I felt that compelled me to take this image."

Should the final output of all of your expenditure, all of your energy and emotion that came with composing, focusing, and exposing your photograph, end just for some false societal idea of aesthetic peddled by some expensively dressed influencer with the word 'tastemaker' in their bio?

I think the majority of photographers in history would say fuck no to that one chief.

So how much should we edit our film photos?

Obviously, a very subjective and personal question. Here are the questions that I've asked myself that has helped me develop my method to my editing my film photos.

- Are there any qualities to the film stock that I'd like to keep that will act as my guardrails for editing?

- Does the story I'm trying to tell require any alterations that go outside these aesthetic guardrails?

- Does further manipulation of my photo go against any moral or philosophical frameworks I have as a photographer?

For me, the qualities of a film stock that I'd like to maintain is the saturation that occurs at different luminance values in a film stock. I don't mind adjusting exposures, working on the shadows, midtones, and highlights, or adding vignettes. At most, I would adjust the color temperature if it feels too off. I'll only maximally try to claw back exposure if I feel like I'm losing the subject thanks to some poor exposure. And after all is said and done, I take a look at my photograph, and ask myself if this falls in the realm of work that I feel let's me call myself a photographer. Sometimes, when I have edited a photo too heavily, I reject my own work, because my tenants as a photographer is try to capture reality through perfect exposure, and to take a breathtakingly human moment. If it takes so much time and masking to make the photo breathtaking, human, or momentous, I didn't do well as a photographer.

So you must make your own tenants as a photographer. You can me a fundamentalist, a purist who shuns any touchups of your photos ever. You can also be a darkroom squatter, dodging and burning to your heart's content. The choice really is up to you – you are the ultimate maker of your own taste.

Comments ()